|

At the age of nineteen I became an atheist and an existentialist. It was my second year of college and I began a habit of spending hours in the library stacks pulling down volumes whose titles promised a new frontier of knowledge. That was how I discovered the holocaust. The first volume I read was the Warsaw Ghetto Diary, which thoroughly undermined my faith in the human race. I followed this harrowing narrative with the similar Vilna Ghetto Diary which further disabused me of the notion that the universe is guided by a benevolent diety. In addition to proving mankind is on its own, these personal accounts provided deep insights into the Nazi mentality and the Jewish efforts to remain unobserved. I had read the Diary of Anne Frank in high school, but by the time her sanctuary was breached her reporting was over. The angst in the ghetto diaries was palpable, and let me to seek corroboration. The histories I found with their black and white photographs of the camps was a vision of the death I was at first unequipped to deal with. Auschwitz was a particular horror, the brutal camps, the all-too-efficient crematoria. I would awaken from my nightmares in a sweat, still gasping for breath from the acrid gasses paralyzing my lungs. The existential angst seemed at its most acute in my self-tortured meanderings as I descended the steps into the antechamber where I was stripped and readied for extermination. The fascination of the camps still taunts me, and I remain to this day strongly lured by stories of unexpected or accidental holocaust survivors. Perhaps none have pulled me in more than Warwick Davis and the Seven Dwarfs of Auschwitz which I recently found on YouTube. The seven members of the Ovitz family of minstrel dwarfs would have been eliminated at the entrance of the extermination camp were it not for Josef Mengele’s “medical”fascination with dwarfs, and Hitler’s infatuation with Disney’s animation of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (from the German fairy-tale Sneewittchen). Warwick Davis bonds with the kindred-spirit performers of the Ovitz family and tours their origins in a remote part of Hungary, He takes us to the cattle cars and the rail platform outside the work camp where the head of the Ovitz brought out a playbill of their performances to take to the SS leaders. Warwick reminds us how the seven performers, just like himself, were world famous acts widely applauded before the war. He takes us on an intensely personal guided tour of the camp with sympathetic docents who show us the sleeping quarters for a thousand inmates impossibly crowded, and the Little Wood, a forest still standing where overflow crowds waited for space to clear out at the chambers. I thought I knew about the Holocaust, but from an empathetic man of small stature I have learned far more.

0 Comments

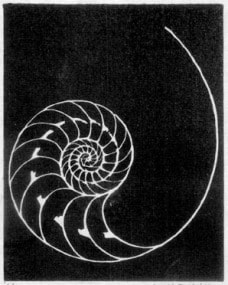

This is one of Earth's most unfamiliar life forms. Like an earthworm, it spends its entire life buried in a food-rich substrate slowly engulfing what comes to its mouth, digesting the sparse food that it encounters, then excreting what is left from the other end. It is a member of a marine phylum of life containing 7,000 species found in all the seas on Planet Earth.

In my late 20's I lived in Puerto Rico and spent as much time as I could beach-combing and snorkeling in the shallow Caribbean coral reefs. I would encounter bizarre egg-like skeletons at the upper tide level, washed there with the sticks and other flotsam temporarily just out of the reach of the waves. These fragile treasures were as light and insubstantial as cascarónes, the confetti eggs children in Spanish-influenced cultures love to smash on their friends' heads at cumpleaño parties. Most were broken fragments, and the few that were intact had to be handled with caution. Like sand dollars on Texas beaches, they were long-dead relics of organisms that made a meager living just offshore. As a youth, I used to shuffle my toes in the sand at my feet on Gulf beaches between the surf-breaking sandbars in neck-deep waters. When I encountered little rough disks I would wrap my toes around them and reach down with my hand to extract them from between my toes. Unlike the smooth, sun-bleached forms found on the dry beaches, they were tan in color, and covered with tiny bristles that waved about in alarm. Usually, I would give them a toss and look for more, but sometimes I would bring them into sandy tide pools to inspect their habits. I would lay them flat in the calm waters and in seconds they would bury themselves by pulling sand grains up and laying them on their top surface, like pulling the covers up as they put themselves to bed. I would lie down next to the tide pool and place them in the palm of my hand to see how they did this neat little trick. Projecting between the spines waved tiny white arms that seemed to stick to my fingers. The spines acted in unison with these fleshy arms to move them along quite rapidly. Sensing their distress, I would take them back to the quiet waters between the sandbars and drop them back home. I remembered these sand dollars as I found these marine cascarónes in Puerto Rico and knew that these marine cascarónes were related to the sand dollars since both featured a 5-pointed star symmetry. I began to look for their living representatives and presumed that like sand dollars they could be found in the shallow sand. As I snorkeled in quiet waters I began to dredge my fingers into the sand and was soon rewarded with the grand prize!I brought to the surface a giant 8-inch sea biscuit nearly 2 inches in depth. Like the sand dollar they were covered with short hair-like spines, but also had a few long spines 4 or 5 inches long, which they brandished at me like menacing swords. Like the sand dollars, they too buried themselves when returned to their habitat, though slower due to their great size. Although it violated my "leave-it-alone" philosophy, I took one of these "sea biscuits" as they are commonly called, and dry-landed it to steal its life and skeleton. Once the corruption of the flesh brought on by its death hollowed it out, I rubbed off the spines and soaked it in bleach to render it white in color. It was so very fragile that I knew I could never add this to my collection of sea urchins and sand dollars that I was bringing together for study. I applied several layers of varnish to strengthen the shell, and was pleased with how strong the result was. I was surprised that this had the side effect of bringing out a pattern of skeletal elements that I had previously seen only the suggestion of. I would learn years later in paleontology classes that the individual ossicles composing the skeleton were single crystals of calcium carbonate. When thin sections of rock samples are subjected to certain kinds of light rays (as geologists are prone to do) these single crystals shone like beacons of their special character.  Dave Webb - Setaria in pocket Dave Webb - Setaria in pocket A monoprint is, as the name suggests, a unique piece of art, not a part of a larger series or numbered edition. The tradition of numbering prints came about in the late 19th century when mechanization of image-making resulted in large numbers of prints becoming available of individual images. Commercial producers, such as Currier & Ives, marketed these prints often popularized from publications in magazines. To distinguish these mass-produced images from their fine art counterparts and make them more attractive to collectors, printmakers began to number their hand-pulled prints as a part of a limited edition. The basis of any print is a matrix which carries the ink to the paper, and when this matrix is stable, such as a metal plate or a block of linoleum, an edition of prints can be numbered from this matrix. If, however, the matrix is unstable, that is, obliterated by the act if printing, or shifts in such a way that pulling an exact (number-able) print is not possible, the resulting print is a monoprint. These are not editioned because each is different and so does not bear a number (1/1 is a mistake in nomenclature). My botanical prints are monoprints by this definition, and they also are a part of a class of prints called direct prints. This is a type of printing in which an object is given a coat of ink, then touched to the paper to draw off a reversed image. The process is similar to a frottage, or rubbing in which paper is placed over an object and a chalk or graphite stick is rubbed over the object to yield an impression on the intervening paper. The main difference is that the monoprint is reversed while the frottage is a correct and accurate rendition. The first prints I ever made, in the early 1990's, were fish prints, or gyotaku (Japanese for gyo - fish; taku - taking an impression). The process is quite simple. Laying a fish on its side first blot off the excess moisture, then apply water-based relief ink with a roller until coated with a thin layer of ink. Then place a sheet of mulberry paper on the fish, a layer of waxed paper to smooth the transfer, and burnish by hand. When the mulberry paper is pulled off, a fine impression of the scales of fish is the result. Of course it takes considerable skill to make the fish print a work of art. Botanical prints could be made in this way, but this would not be very effective. My method involves several steps. First the plant is pressed in herbarium press between newspaper and corrugated cardboard until it is dry and flat. This may involve several changes of newsprint if the plant material is full of moisture, and may take a month or more. When that is done I bring the specimen into the print shop. I take a sheet of plexiglas and roll out a thin layer of ink with a large roller. This ink is not the aqueous ink most people know from fountain pens, but rather a thick ink with the consistency of toothpaste. I carefully place the plant onto this inking platform so as to minimize overlap of the leaves. Covering with newsprint, I run this through an etching press. The pressure (about 600 lbs per square inch) drives the ink into the matrix of the plant. If some leaves overlap, they are repositioned and run through the press a second time. If that plant were delicate, say a rose petal, this process would destroy the plant material, rendering it useless for the next step. For this reason the plant must be rather sturdy. Ideal subjects are grasses which possess in internal architecture that keeps the structure intact. There are parallel veins which act like little I-beams to preserve the leaf blades. The roots, too, are usually very strong, so impression of the roots can be very intricate and beautiful. Once the plant has been run through the press, it is imbedded into the ink layer, and must be delicately pulled up without breaking. This generally involves forceps and needle probes to extricate the plant in order to keep the specimen from fragmenting. When it is free of the bed of ink, I carefully flip it over and lay it onto a clean sheet of plexiglas, inky side upwards. Once positioned I use cotton swabs to place ink in any areas which did not take up enough ink, and clean the plexiglas of any stray marks which may have been laid down when the plant was positioned. Taking a dampened piece of printmaking paper, I gently let it fall onto the inked plant. If it falls incorrectly, there is no possibility to reposition, so this step must be carried out precisely. When the paper is resting on the inked specimen, I cover with newsprint and run through the press to produce a print. This is laid on a drying rack or hung vertically on a rail suspended by magnets for a day or two before it can be safely handled. I think of it as a fossil of a plant on paper. I use various kinds of paper for botanical monoprints depending on the type of plant and size of the specimen and the final effect I am striving for. For larger prints up to 44" the paper must be robust, such as BFK Rives, a fine absorbent paper from France with a weight of 250 or 275 gm/m-2. Somerset from Britain is a similar high=quality paper I sometimes use. This paper must be dampened before printing to form to the specimen and transfer a good quantity of ink. Dampening has the additional effect of embossing the paper with the form of the plant, a process that lends a subtle sculpturing and contouring that makes it seem as if the plant is actually present as a three-dimensional object. For a more delicate look, I use thinner papers: Japanese mulberry papers such as Kitakata, Hosho, or Okawara impart an Asian look to the result while brightly pigmented Tibetan papers like Lokta have an impactful saturated appearance. These thinner papers are run through dry and thus hold less embossing. I mostly sign these prints on the back, preserving their character as reports from the biosphere whose true creator is Mother Nature. Thinner papers would show through, so these I mostly sign on the front. I try to title them with the Genus and species of the plant, but this can be a challenge since the grasses are difficult even for grass specialists who must examine tiny flower parts under a dissecting microscope.

My block prints are cut into a matrix of linoleum, a material that is easy to carve and holds up to making multiple prints. The concept of multiples is a source of some confusion to beginning art collectors. A painting is an original, and if a copy is made, that copy is a reproduction. Quality reproductions can be made by various means, but there is still only a single original in painting. In printmaking, if the same logic is followed, the block itself would be the original, but this is in reverse, so the block itself is not very collectible. The product in printmaking is the print, and these are numbered into an edition. In a limited edition print, there are normally not more than a hundred prints, and each one is an original. Since there are multiple originals, they must be made as close to identical as possible, within the limits of printmaking art. Reproductions, on the other hand, are produced by machine, so they are exact copies, not originals.

My linoleum block prints are very finely detailed, and this level of precise cutting is accomplished because I work under a stereo dissecting microscope. This process requires some delicate skills which I honed with years of working under the microscope as a biologist. I worked with Drosophila melanogaster, the fruit fly barely a couple of millimeters in length. The various strains of interest are distinguished by minute differences of many traits, such as eye color, forms of the small body bristles, changes in the pattern of the wing veins, and many other tiny variations. The skill of working under the microscope with small organisms transferred to cutting on blocks with small cutting tools, so I am able to produce fine blocks that would be a great challenge to most artists. My first prints were linoleum block print replicas of classic postage stamps. Later I began to produce prints with more original designs. . How many times did I amble down this "back alley" to my apartment? Twenty five years is 9125 days, and I surely passed along this sidewalk at least once a day. Now only the untethered leaning telephone pole and ancient oak remain, my former home, ... gone. The maintenance shed whose roof my bedroom looked out onto. ... gone. Even the sidewalk, ... gone. My life at Wilshire Village, ... gone.

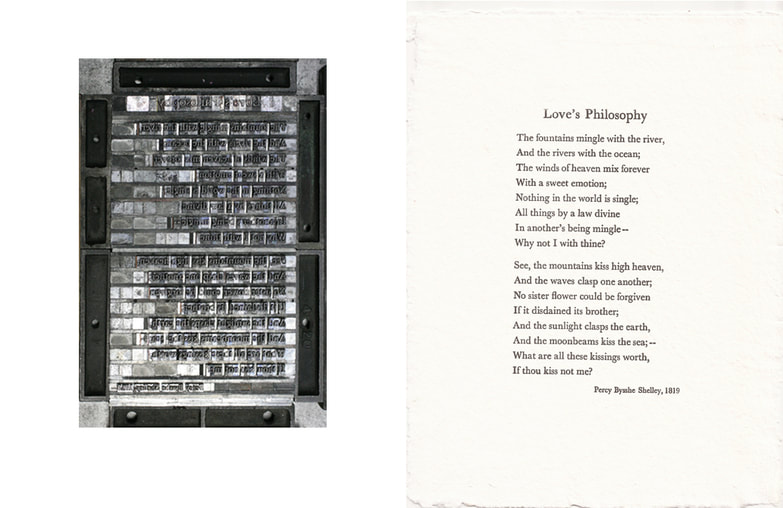

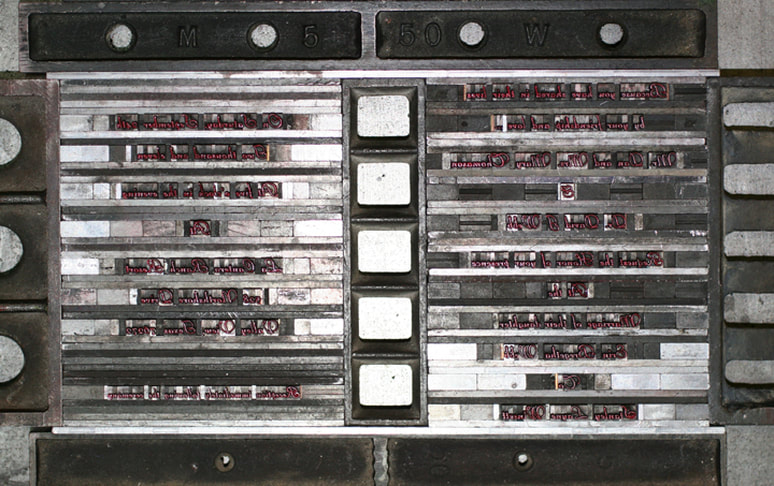

I had been volunteering at the Museum of Printing History for more than a year, accumulating studio time to work on book arts projects. I was finally ready to to set my first type, and wanted to start with a modest project. A single page of text would he a good beginning, and a succinct and meaningful poem would be ideal. All the past fall I had I had been watching episodes of Inspector Morse and its successor, Inspector Lewis, on PBS Masterpiece Theater, as much for the wonderful poetry by A. E. Housman and others as for the drama of the series. The action takes place at Oxford University where multiple murders must be solved without disturbing the dreamy academics. In the episode "And the moonbeams kiss the Sea," Percy Bysshe Shelley's poem, Love's Philosophy is found in the pocket of a murdered art student. An early suspect is another artist with a quirky personality, perhaps somewhat autistic. He seems unaffected by the murder of his friend and lover, is amused that the police have found a "body in the Bodleian," the ancient library at Oxford holding manuscripts of English poets back to Shakespeare and Chaucer. Oxford is the university of my fantasies, and any drama set there is sure to charm me.

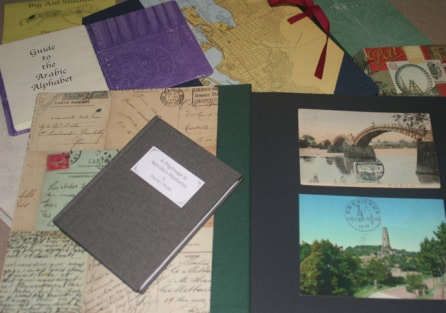

For weeks after seeing the episode my mind was full of the Romance of Shelley's life and early death, his passionate loves and committed atheism. The end of the episode finds Inspector Lewis at the Shelly Memorial on the Oxford campus marveling at the icy cool sculpture of the drowned Shelley by Edward Onslow Ford. My first project would be the love poem of Shelley's youth. The first decision was to choose an appropriate font. I wanted it to be from the times when the poem was published in 1819, but that was not the only restriction. It also had to be present in three sizes: title, body text and present in the museum's collection in sufficient quantity to account for all the letters. The font called Baskerville was a classic early 19th century font that filled the historical requirements, and there was enough of the 11, 12 and 14 point foundry type letters to accommodate the poem. The second decision was the choice of paper. A machine-made paper would not be distinguishable from a printout from a computer printer. I chose instead a handmade paper made of abaca fibers by the papermaker at the museum, Kathy Gurwell.The paper was a soft paper with a lot of individual variation, and was a lovely shade of beige. Every sheet bore a deckled edge, and the size of 8.5" x 11" left a generous amount of paper surrounding the poem. The third choice was which press to use, one of the Kelsey platen presses, the Washington press, or the Vandercook proof press. The Kelsey is self-inking, so it would be faster to print a large number, but I only needed 25 copies and did not mind hand inking. The Washington is a little harder to register each sheet, and requires more muscular effort per sheet, so I chose the Vandercook. Each sheet is fed into the press with a rolling motion, so the work flow is smooth, and the hand inking would not be a chore for twenty five copies. The fourth choice is ink, and the alternatives are rubber-based offset ink and oil based printing ink. Though rubber-based ink is slower to dry, it stores on the shelf longer for intermittent printers like myself. I normally use rubber-based ink for my linocut prints, so I stayed with that. Foundry type is stored in drawers (cases) filed with a California case layout. I opened the case and with the compositor's stick in my left hand, placed the letters upside down (nick up) into the stick in the order of the text. After each line I checked the tension by adding thins, combinations of brass (2 points) or coppers (1 point) until the letters no longer had any slack nor were too rigid. Setting the entire poem was an afternoon's work. When the lines are turned right-side up, it reads backwards, as it must to print the correct direction. The following day I arrived early with my paper, ink, roller and cleanup materials in hand. Printing was almost anti-climactic, and in just an hour or so I had all the copies I wanted. These went onto the drying rack, and when I returned the following day the copies were thoroughly dry, and I redistributed the type back into its proper cases. I consider myself a serious reader, and have read most of the landmark volumes of world literature and philosophy. Like most of my generation, however, I have been a victim of the paperback revolution. Since most of what I have read are paperback versions, I have had little exposure to books as objects d'art. I have taken books for granted, evaluating them solely on their verbal and/or visual content, only occasionally taking note of any other aspect of their design, materials, or production. This began to change one summer session when I was a physics undergraduate. Bored (or perhaps overly challenged) with the tedium of electromagnetic theory, I amused myself by reading Victor Hugo's Les Miserables. The lengthy novel overtook my life, and soon I was skipping classes to stay in my dormitory and read. The books themselves were from a limited edition of small volumes published in 1894 by G. Barrie in Philadelphia, containing many fine hand-pulled etchings tipped into the volumes at frequent intervals. I became so diverted from physics that I abandoned LeGendre's polynomial, the equation explaining an electrical charge on a sphere, in favor of Jean Valjean and his beloved Cosette, Inspector Javert, and most intriguing to me, the old revolutionary, G----. That summer I flunked out of physics and changed my major to English. I began to seek out hardbound books, spurning paperbacks whenever I had the option. My love affair with books began in earnest. but I was still not a very savvy critic. I loved the feel of a good book, the heft of a thick volume in my hand, the feel of good paper, the way the pages turned. I hardly noticed the details of book manufacture. I admired marbled endpapers, but didn't ask questions about their production, and had no sense that they were made by craftsmen. I never connected the stitches with a human hand pulling a needle through the paper, and presumed that task had been entirely mechanical. When I became a printmaker, I started to pay more attention to illustrations as an integral part of book content. I purchased illustrated hardbound books when I could afford them, but still considered books a manufactured object rather than a fine art production. That changed when I began to study bookbinding. At first we constructed books without content as straightforward structures. Soon, however, I began to realized that a book could be constructed entirely by hand from its raw materials: bookboard, thread, cloth, paper, glue. New horizons of creative possibilities opened up to me. A Guide to the Arabic Alphabet A Pilgrimage to Melville's Manhattan Two in Arcadia When my daughter announced that she was getting married, I was elated. Her intended is a fine man who cares about her and is dedicated to his daughter. I will be pleased to have him for a son-in-law. After the news sunk in, I wondered how I could help with the plans. Fathers of young brides have historically been tapped to pay for the event, but in the modern era of self-reliant women who often marry only after establishing themselves, this practice is often set aside. In any case my monastic lifestyle rules out a significant role in the financial aspect of the celebration. But I wanted to contribute in some way, and I soon realized that I could lessen the burden by printing the wedding invitation as a letterpress project. I was delighted when she agreed that I could take on this task.

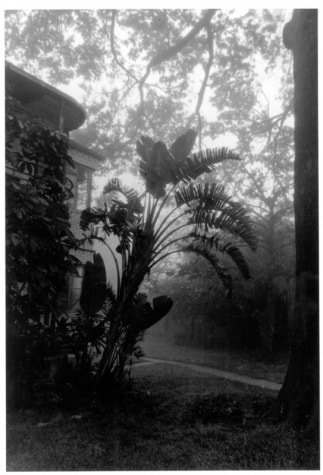

I have been a printmaker since 1998, and have been volunteering at the Museum of Printing History since my exhibition there in 2008. My first letterpress printing there was a poem by Shelley done in December 2010, and I was anxious to extend my experience at the art of text and foundry type. We consulted back and forth on the text of the invitation, the paper, and the font and after six weeks of communiques I was ready to set the form. We had picked Liberty Script, a fine font which the Museum had in abundance in 14 point and 12 point, the sizes I needed for a line length of 20 points. At 72 points per inch, a 20 point line is 3.6 inches. I set the type upside down with the nick up in a compositor's stick held in my left hand as I pulled the type from the case with my right hand. Thus, when the stick is turned upside down, the text reads backwards as it must for printing from lead font. Since the text was to be center justified, I placed an equal number of spacers of whatever sort I needed (quads, em-spaces, en-spaces, etc) on both sides of the text, then adjusted the tension with thins of 1 point (copper) or 2 points (brass) until the tension was just right before moving on to the next line. When all the lines were set, I placed the form (the type to be printed) on the bed of the Vandercook press and placed furniture around the text, including horizontal and vertical quoins to tighten the text and prevent slippage during the printing process. I planed the letters by tapping with a rubber mallet to make sure no letter stuck up too high, checked that there was no lateral slack by pushing backwards and forwards, then tightened the quoins to secure the form on the press bed. I inked in red (Pantone 199) with a hand roller, and printed on Fabriano Medioevalis. My neighbors, Linh and Kris, tended a lovely garden at the foot of their stairwell for many years. Protected by the canopy of a grand willow oak, the fan palm grew slowly larger as the years accumulated. I often admired its graceful curves, never more than on one foggy morning just before tenants at Wilshire Village were evicted and the complex abandoned. Returning a year later, I found the peaceful spot utterly demolished, no trace of the palm, the garden, the buildings, or the lives of my neighbors once so happily nested there. Even the overarching willow oak had been damages, some of the branches amputated by the clumsy machinery of demolition.

The Fan Palm would have surely perished in the winter of 2009 / 2010 in any case, so brutal a weather reminder that Houston is actually not a tropical city. Banana Fan Palms are originally from Madagascar, now grown throughout the tropics. Ravenala is the botanical genus, more prosaically, Traveler's Palm: Arbre des voyageur (French), Waaierpalm (Dutch), Baum der Reisenden (German), Arbol del viajero (Spanish), 旅人蕉 (Chinese), Chuối rẻ quạt (Vietnamese), although I favor the more poetic Urania to the dire-sounding Ravenala, Urania (Οὐρανία) was one of the nine muses of Greek mythology (The others were: Calliope, Clio, Erato, Euterpe, Melpomene, Polyhymnia, Terpsichore, and Thalia), known as the muse of astrology. She was most often depicted as gazing heavenwards, wrapped in a star-embroidered cloak. In Classical times she was muse of philosophy, and after the Renaissance, muse to the Christian poets, most famously the "heavenly muse" from Milton's Paradise Lost.  I was in Brooklyn for the day, looking for something to do while my daughter was busy with her internship with John Jay College of Criminal Justice, CUNY. We’d be spending the evening together, but until she finished her court visitations around four o’clock, I would be on my own. We quickly shared a coffee together at the plaza in front of Borough Hall, then parted company. I headed immediately for The New York Transit Museum a few blocks away, anxious to see the museum that chronicled the transit system that created America’s greatest metropolis. When I tried the door, I was irritated to find it securely locked - the sign indicating that the museum opened at ten o’clock. I circled the block, looking for other points of interest in the area, and wandered into an opulent hotel lobby. By the time I found my way back it was not quite ten, so I waited at the entrance. They opened promptly, rather surprised, I thought, to find someone so anxiously waiting to get inside. As a new admirer of subways, I was interested to see the extensive collection of antique subway cars arranged in chronological order. Finding the section from the 1930’s, I sat on the pew-like seats and imagined myself as Walker Evans concealing my camera in the folds of my overcoat while photographing fellow travelers. The Museum Shop was tiny, but they did indeed have the transit map umbrella that I had wanted, my single concession to tourist memorabilia from my trip to New York. Released back to the city, I set out in search of brownstone buildings now more abundant here than on the island of Manhattan. Brooklyn was much more prosperous than I had imagined. I had thought it might be a little tatty at least, but it was definitely very upscale, clearly unaffordable to me. I quickly deluded myself of the fantasy of moving to Brooklyn, finding cheap accommodations, and settling into a life in proximity to the City I was beginning to love. In search of views, I wandered toward the East River where there should be a splendid view of the financial district. Sure enough, I soon encountered what is famously known as the Brooklyn Heights Promenade, though I was completely ignorant of it. The view of lower Manhattan was splendid! Elbowed at both sides with fellow tourists, I took a few photographs from the fence, but they were mundane, cliché snapshots. I stepped back a few paces and squared in the wider scene through my viewfinder - much better! The foreground figures recapitulated the erect structures on the far shore, and the black bannister-like fence formed a unifying horizontal element that tied the foreground to the background with graphic harmony. Interesting! ... I snapped the shutter. The Hotel Alex Johnson The Alex Johnson Hotel logo The Alex Johnson Hotel logo 23 January 2013 was the 30th anniversary of my father's death. I still miss the guiding influence has had over my entire life; he was for me a barometer of what a man should be. He continues to have influence as a benevolent and loving voice I often hear when I am in doubt. "What would Father say?" is a question I still ponder. His voice was never stronger than I heard it on 16 July 2002. That summer my sister Mary organized our periodic family reunion to be held at Sylvan Lake in the Black Hills of South Dakota. It was to be something of a sentimental journey for me. I had lived in South Dakota from 1956-1963 while father worked at the Edgemont Uranium plant where he was the general manager. We often went to Sylvan Lake for summer vacations, and my sisters Ethel and Diane sometimes joined us there for weeks at a time. So Sylvan Lake was a per The first leg of the journey involved a plane trip from Houston, Texas to Rapid City, South Dakota. I arrived at the airport quite fatigued. I had booked a departure from Houston at 7:40 AM, and spent the previous night trying in vain to sleep on a very hard bench at baggage claim. My plan was to spend the night inside the terminal, but I had failed to understand that only ticked passengers with a boarding pass could enter the security cordon protecting the comforts of the terminal proper. Ticket agents could not issue boarding passes until they opened at 5AM, so I was forced to find a spot to wait outside the security zone. I had not flown since before 9-11 when everything changed at airports in America. The flight was uneventful, and far briefer than the time I had spent listening to passengers collect their luggage from red-eye flights in Houston. I had slept most all the way on the jet, aided by a dose of Zanax I had taken as we left the ground in Texas. The entire Rapid City airport could have been set down in one corner of baggage claim in Houston. Exhausted, I had a hard time collecting my thoughts as I disembarked. Energetic tourists in leisure clothes bustled about their hurried schedule, and crisp terminal workers had a casual look even when wearing the standard corporate uniform. Everyone was talking about the heat. There had been a heat wave, and the mid-afternoon temperature was hovering about 102 degrees. They spoke in an accent with a tempo and twang that I had forgotten. It sounded comforting and familiar, like suddenly meeting up with a childhood friend for the first time in many years. I ventured outside to catch a glimpse of the Black Hills, and the heat was palpable, so dry that it was not at all unpleasant. The smell of dried grass suffused the air and I took in deep breaths as I examined the low rise of dark hills to the west. This was not the stark, soaring of splendor of Colorado where we had gone for Mary's last reunion. It was gentler, more human and oh, so familiar to me. Back inside, I loitered around the baggage claim area waiting for the bags to clear. Rather than wait at the revolving conveyor belt like all the other passengers, I wandered over to the advertising kiosks placed along the wall. The spired Alex Johnson Hotel advertised as the premier hotel in the town of Rapid City, looking very western with its cowboy-culture decor. The picture poked at me like a memory trying to gain re-entry into my mind. Was this the place I remembered from my early adolescence? An elderly lady jostled me in her aggressive haste to get at her bags, and my reverie was broken. I was in no hurry and did not want to jostle with those anxious to be gone, so I hung back. Though I would have been content to be the last to leave the baggage area, my bag was among the first to show. I reached over and removed it from in front of the impatient lady. At the rental car booth I stated my reservation number and filled out the final forms. Directed to the parking lot, I found the car and settled into the seat. The impatient lady emerged from the building with a girl and young man and who carried her bags. They filled the trunk with her luggage while they expended a great deal of excited chatter. I felt tired from the sedative, and glad that I did not have to force myself to be conversational. I idled the car and made sure I knew where all the pedals and knobs were situated. I owned no car and seldom drove, so I had to acclimate myself to the alien terrain of the automobile. At length I was in motion and on the freeway into town. A bicycle would have been dangerous on this road with no shoulder. I wondered if anyone here in South Dakota preferred two wheeled transportation, and if that was even possible. The drive to the Motel Six where I had a reservation was mercifully brief, and once there I lay down on the bed to relax. When I awoke two hours later, it was too early for dinner, and I was too restless to hang around the motel room. I remembered the historic Hotel Alex Johnson and resolved to go out in search of it to see why it seemed so familiar. I didn't look at the map, I just started driving, but somehow seemed to know what streets to take. As I approached the downtown district, I could easily see spires and distinctive, almost alpine roofline of the hotel - the tallest building in town. Though a regional urban center, there was little traffic of the kind I was used to in Houston, and I was easily able to park within a block of the compelling edifice. I pulled into a convenient parking space and got out to go over and get a closer look. I felt drawn there, somehow certain of my steps and intent upon my destination. Rounding the corner, the first floor facade brought a flood of memories from so many years ago. Suddenly, I remembered being with Father who was in town on some business he had just concluded. Mother and my sisters were out shopping, so it was just me and father, four or five in the afternoon, and he says, "I want to take you out to a dinner at a special place." At the intrusion of this memory, I suddenly realized this was the same building where we had eaten so long ago. Would there still be a restaurant? "Unlikely," I thought, but I determined to perambulate the block to savor the experience before seeking out a Waffle House or some similar inexpensive eatery. At the corner, though, I was stopped by an impressive entrance door. It was a carefully hewn of fine wood and obvious quality. This was a more expensive restaurant than I usually patronized. Stickers proclaimed affiliation with Diners Club, MasterCard, and American Express, so I would be able to charge the expense to my vacation. Certainly, there was still a restaurant here, but surely it could not be the same! That was forty years ago! I hesitated at the threshold. It was early for dinner, and a hotel restaurant might well be closed during mid-afternoon. Nevertheless, I tried the door. The handle was heavy and luxurious, and as I pulled to open the door, I was drawn into a veritable time machine. It was indeed the same as I remembered! My memories filled in the interior contours with complete accuracy. I couldn't believe it! The attractive young hostess approached me with cheery greeting, a menu, and a gesture into the dining room. I motioned to the other side, an aspect that seemed somehow most familiar. "Can I sit there?" "Yes, of course. Please, sit wherever you like." She brought me into a narrow alcove with a banister which overlooked the hotel lobby. There were only three or four quite empty tables, and I requested the table at the end, the one with the best observation of the lobby. I took my seat and looked up at the wagon-wheel chandelier and Native American scrollwork. I slowly scrutinized the menu. Prime Rib, the most expensive dinner in the restaurant, beckoned forcibly from the pages, and suddenly I was flooded with emotion. I remembered father's dinner as if it was yesterday. He said to me, "The food here is really good. The prime rib is excellent." "I don't feel like bones." He laughed good-naturedly, "Prime rib doesn't have any bones! Order it medium rare and it should be very tender and juicy." I felt embarrassed by my ignorance, but father was not making fun of me. He probably had a martini earlier, that usually put him in an expansive mood. He had finished with a business meeting earlier in the day, and it must have gone well as he was feeling generous. I remember father as he stretched out his legs and admired the ceiling. Strange that he has been dead for twenty years now, yet in my memory he is as alive and full of character as if he were in front of me. Mirroring father's gesture, I looked up at the painted ceiling of today. The paint seemed fresh enough, perhaps at least a few years old, maybe more. Was it the same as what my father saw? The waitress came back to see what I would have. "Have you decided what you want?" "Do you have Prime Rib tonight?" "Yes." "Let me have that, medium rare." "Baked Potato?" "Yes." It had been a long time since I had baked potato with all the fixings, too much saturated fat is bad for my cholesterol. "Salad Dressing?" "Blue Cheese." I won't be worried about cholesterol for once. She retired to leave me to my solitary musings. Separating the restaurant from the hotel proper was a half-wall with etched glass. The lobby was small and intimate, a few heavily stuffed leather chairs placed casually here and there for hotel guests. My memory was becoming sharp. The decor had not really changed at all. I pulled out my notebook and sketched the A-J-H logo from the back of the custom-made chair opposite. My father's presence became palpable, almost as if he were looking over my shoulder. My eyes filled with tears. 'Good god, get a grip,' I thought, 'Don't start crying here!' The waitress returned with the salad and placed it in front of me. I hoped she hadn't noticed that my eyes were moist. I savored each forkful of lettuce, lingered over the blue cheese. Suddenly, I realized that I was not sad at all, there was no need for tears here. This was a precious chance to commune with my father and with my past. I visualized my father sitting opposite. I could make out his senatorial profile, the languorous command he always had over his large-framed body. In my mind he turned to me, as if to answer a question. I was always asking him for advice. He seemed to know what people could be counted on to do. 'Am I on the right track?' was my silent question. 'Yes, you are doing fine. Your life has been harder than I had thought it would be, but you've done okay. You had more happiness than you might have had.' 'What about my being gay. Are you all right with that? We never had a chance to talk about that.' 'Remember, your mother was only sixteen when she got pregnant, so you should understand that in my youth, I was driven by sex as much as you were. Neither of us were thinking about consequences, and although your choices were ruinous for your health, my choices had far reaching consequences as well. From my perspective in the hereafter, your brand of sex is not so very different.' His tone switched to the fatherly mode he adopted when about to give advice, 'We are just two souls now, son. While I was alive I didn't understand gay sex because I never knew anyone who was queer. Everyone thought homosexuality was perversion, and I would not have wanted a pervert for a son. I see things more clearly now. Because nobody ever talked about it, I had the sense that sex was something dirty. You never had that kind of "hang-up," as your generation calls it. You led a very promiscuous life compared to me, and I suspect that kind of promiscuity must have been very seductive. It offered temptations any man would have found attractive. I can appreciate that now that I'm dead. You are not so strange to me as you have been thinking for so long.' In his living form, father was quite a prude, and any kind of sexual talk would have embarrassed him to the point of blushing. He didn't live long enough for the two of us to have an adult conversation about sexuality, neither heterosexual nor homosexual. All the same, I always had a sense that he knew what lust was all about. Unfortunately, in life he could no more have spoken about it to me than he could have discussed it with his parents. Of course, my relationship with my father didn't end when he died, and having this conversation was very soothing to me, even if I was inventing both halves of the dialogue. My prime rib arrived, and I set aside my conversation with Father. I picked up my fork and savored the tender meat. I lathered three pats of butter onto the baked potato and heaped it with bacon pieces, cheese and chives, like I was a kid again. No child myself now, I had turned fifty four just ten days earlier. How long ago was that first dinner here? It must have been the summer before we went to Texas. That was in 1963, so Dad's prime rib dinner would have been in 1962. I seem to remember some vestige of snow on the streets outside, so it must have been early in the year. Since I was born in 1948, I would have turned fourteen the summer of 1962, so I would still have been thirteen then, right on the verge of manhood. How old was father when I had the prime rib dinner at the Alex Johnson? He was born in 1907, let's see, ... In the spring of 1962, he would have been fifty four. My God! A chill went down my spine, and tears came to my eyes. I just turned fifty four! I am at the same age now that father was then! Father smiled back at me knowingly. A visitation indeed. Thank you father. |

Author I'm a seventy something old codger retired from an all-to-brief career as a scientist and educator. No longer bound by the constraints of having to make a living, I have turned to the arts to amuse myself. My work consists of "works on paper" including prints and photographs, as well as letterpress and book arts. I write for my own amusement and read whatever books I find interesting from Proust to Melville. Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed