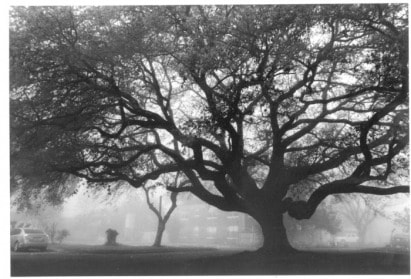

Wilshire Oak in the Fog

Wilshire Oak in the Fog The price was right at $282 a month, but the complex was a coming apart at the seams from neglect. Clearly maintenance was not a priority here, and the management was aged, if picturesque, and almost certainly ineffective. It might be nearly impossible to get anything repaired if there were a breakdown of the window unit air conditioners or dangerous gas space heaters. But there were two large bedrooms, and when the kids came to visit there would be ample room for them to have a semblance of the family life that had been so recently withdrawn from me. It was so peaceful here, perhaps the serenity would put at bay the virus inside they said would kill me. Here I might have more time than the two years they predicted.

I formulated how I would say, "No, not right now. Can I get back to you later?" But I knew that if I didn’t take it now, it would be gone while I looked for a smaller but more comfortable apartment. I was taking a bit of a chance, but I spit out, "Yes, Mr. Hammond, I’ll take it."

***

Now, in March of 2009, twenty five years later almost to the day, I stood in my empty apartment once again and looked out onto the courtyard through the same window. It was little changed. The oaks shaded even more of the court, and the sidewalk had buckled still higher from the encroaching roots. Stained and rotting curtains shrouded apartments long vacant and the multiplicity of broken windows testified to the sad final dilapidated state of Wilshire Village. I remembered Mr. Hammond, now long dead, just as I thought I would be when I told him I would take it in 1984.

My gamble had paid off. Instead of dying here in my bohemian Xanadu, I was walking away alive, although feeling a little bewildered. Here I had faced down AIDS and defeated the disease through sheer force of habit. Here I had created the only real stability that my children knew from their peripatetic childhood. This place was their anchor through their mother’s many moves, their summer retreat with an eccentric but loving father. It was my retreat, too, my refuge from fears of mortality, and yes, my excuse not to expect more of myself.

I thought I would be despondent at leaving this place that sheltered me through much of my adult life. Instead I was leaving here eager to face the future. For the first time in a long time I wondered what the shape of my life would be. It made me a bit giddy to contemplate, but I knew whatever I became, it would be shaped by my years here. I will miss Wilshire Village, but at least I took a lot of pictures (Click on the oak tree for more images).

Basil 5:48 - This is a sad story about the deaths of two cats and the effect on their owners.

| 9 May 2017 Basil died at 5:48 AM. I know because my fingertips were dug into his ribs at the moment his heartbeat died out. My hand had been on his chest for his last moments as I felt his breath falter and stop, then his heart fade in diminuendo until it fell silent. He gave a few kicks in protest then fell limp in my hands. Terry had watched in horror, as much at my intrusion into Basil’s last moments as his understanding that our cat was dead. I looked at the clock. I don’t know why. I suppose I was mentally putting a capstone on his travel through my life. It was 5:48. Somehow that seemed important, … portentous, even, in some unknown way. I lay him back in the chair and wept in Terry’s arms for a long while before I extricated myself to go to the garage and get the shoe box I had set aside when it was clear my dear feline was not going to be with us much longer. I put the box on the round table in the back of the garden and went to fetch Basil’s tiny frame. I cried more when I curled him into his final pose, and closed the cover. I opened it again and looked at my beloved pet whose death we could not forestall. He seemed so lonesome there. In some sense I did not fully understand, I wanted to go with him. But that was absurd, I wanted him to live through me whatever fabulous adventures remained to me. Just putting him in that box was so final, I needed a connection to link my spirit with his. Something to put in the coffin to connect us, some token of my affection for his pure little Zen spirit. I looked around for some natural object, a stone or a stick to put there beside him, but I soon realized that these objects from Nature had no connection to me, and could not link us. I went back into the house in search of a votive with a more personal connection to me. In the kitchen I found it, a wishbone from my last meal. The night before, when Basil was failing sharply, but still living, I had taken long minutes to clean the bone with my teeth and tongue until it was a pristine thing, something to cleanly make a wish upon. I brought it back and laid it next to him. Yes, this will connect us now, I can let him go. Somehow this made losing him comprehensible. I went on my routines very sad that day, but with few tears. I can’t explain the connection I always had to Basil. He looked at me with a penetrating feline serenity. The look always reminded me that we were just two animals safe with each other, neither more important than the other, two spirits linked by trust. |

I thought of the day we buried my mother in 1982. The funeral had been somehow just a formality, a convocation of mourners without much connection to my dead mother. Later as I sat in her lawn chair at the house, surrounded by my family suddenly grown quiet, I looked into the empty Arizona sky, so deep and blue that one could get lost in it forever. I became aware of a single tiny cloud racing across the great dome of the sky. “The desert air will soon take this evanescence puff of moisture,” I thought. “How long can it last before it vanishes?” I wondered. I watched it sail intact across the firmament until the horizon ate it up, leaving the sky completely featureless, a cloudless void. Somehow I knew it was a message from mother, “I am on my way. Do not trouble about me any further, I am all right. Goodbye, my beloved.”

| Then he began to find more awkward places to perch himself. We would find him sitting on all fours on top of the vacuum cleaner for hours at a time. We would look for him and not find him anywhere, then he would just show up. When his long absences made Terry think he had slipped outside, a shake of the dry cat food container would bring him out in a hurry. But he began to lose weight. We took him to the Dr. Rossi and she found a profound bone-marrow suppression, but no cause. She prescribed Prednizone, but he hated it when we brought the towel out and enclosed him papoose-like. Mostly he spit out the medicine, but we kept at it. He became a shadow of his former self, close to emaciation. He begged to be let out, but we kept him because the veterinarian said he might be at risk of feline leukemia or feline immunodeficiency virus. Tests were always negative, but why was he failing? One day he slipped through our legs and ran across the street, and we could not entice him back. Terry fretted all night and into the next day, finally bringing him back home after nearly a whole day. Terry was incredulous, “He was just sitting on top of the fence, and just sat there as I picked him up. He didn’t try to get away.” But it was hopeless, and we could not keep the Angel of Death from taking him away at last. Now, barely weeks later, Zinnia was beginning to exhibit the same symptoms. We first took her to the vet on Friday, June 9th and only later realized that it was a month to the day after Basil died. After a few days, nothing seemed to change so we took her back on Tuesday, June 13th when the doctor tested her for Feline Immunodeficiency Virus and found she was positive. Now Basil’s illness finally made sense. Although he was tested twice for FIV he was negative, but now it seemed cleat that these were probably false negative results. He was almost certainly infected with FIV as well, and both probably from birth. Their fate was sealed from the moment they were born, and when Terry picked them up at Barrio Antigua, they were already destined for shortened lives. |

She had a purr like a hummingbird, so soft it was hard to hear, but high-pitched and somehow rather insistent. She had an engaging way of standing on her hind legs, balancing herself with one front paw while reaching up with a the other toward your face, as if to caress your cheek. Then she would rub her head against your skull in a sort of Eskimo-like rubbing kiss with her snout.

As Basil lay dying in Terry’s chair on the porch, she seemed unconcerned at first. I really didn’t think she understood what was going on, but maybe she comprehended more than I thought. Near the end of Basil’s life when he struggled to breathe, she seemed to stare at him from a few paces away, a curious expression crossing between her whiskers.

After he died, at first she didn’t seem to miss him. At least she didn’t appear to be looking in vain for him. But she definitely sought us out more often, and came to sleep atop Terry’s hip, or cradled in his arms. She wasn’t moping that I could tell, and still ran around the house on her various missions. I never heard her leave the sleeping porch before I was up and out of bed, but by the time I sleepily made it to the kitchen, there she was looking up at me expectantly to do the right thing.

“Stoic,” Chris said, “Cats will put up a brave face, and seem to be trying to look healthier than they are.” Chris was our cat-whisperer, a plain-spoken woman who loved cats and to whom we had often turned to for cat advice. She didn’t tell us outright what we already knew: Zinnia was dying. Our feline companion was stoic indeed, and kept up her daily routines like a good soldier, but she spent most of her time under the bed, where Terry placed a towel in case she peed. Basil had hidden out only a few feet away on the pile of clothes in the armoire, but his nest of clothes had long ago turned cold.

She said it was time. We knew from Basil that it was cruel to wait it out. We needed to act while she still had her dignity. We called the vet and asked her to come out to euthanize our Zinnia. She couldn’t come until the next day. So we waited. Terry spent her last night mostly on the floor beside the bed, his arm stretched out to comfort her. I stepped in from time to time to check on the both of them, but Terry had it covered, and seemed to need this parting gesture.

June 21, 2017.

Just six weeks and a day had elapsed since Basil died, and the vet and her assistant were at the door. I wanted to shoo them away, but knew that this hard thing must be done. I had stood by while Basil failed on his own, and I was resolved to give Zinnia a better death. Eu-thanasia. A true death, a good death. As a moral actor, this was far harder than being a dulled out bystander. It is one thing to stand by while Nature takes its inevitable course. It is entirely a different moral character to be the agent of death.

When I was about twelve we went camping on Lake Sheridan in The Black Hills of South Dakota. Ethel, my sister sixteen years older, came up from Texas bringing Luke, her husband, and the kids, Kay, Debbie Sue, Marty., and she was pregnant with Peggy. We spent a couple of weeks in midsummer nearly every year. The Texans needed relief from the scorching summer season in Midland, TX. Kay and I had found a magpie nestling fallen from the nest and abandoned by her mother. We adopted it and fed it the entrails from our fish catch. Kay and I were the official fish cleaners. It was an opportunity for me to do scientific explorations and report on what the fish were eating so Daddy and Luke could adjust the bait. The magpie got fat on our more than ample diet, and Kay and I thought we were giving life to a baby creature that would otherwise have starved to death. The magpie followed everybody around cheeping loudly for food. But one day somebody stepped on the bird and broke its neck. Daddy insisted that it “Would have to be put out of its misery.” I cried out, “No,” but Pappa took his fishing knife and cut the tiny thrashing bird’s head off. I was devastated. I sulked for days, and would not speak to my father for the rest of the time on the lake. I was mean to Marty, who I blamed for stepping on our magpie, and even now he probably doesn’t know why he doesn’t like me. I eventually forgave my father, and accepted his wisdom if not his method of euthanasia.

Zinnia had hardly moved from Terry’s knee for many hours, and she took up her position there on the floor of the bedroom for her final moments. The doctor had some trouble finding a vein for the sedative that prepare Zinnia for the coup-de-grace. A few minutes later she went slack, and the final shot administered. First she was quiet, and then she was still. The Doctor checked for a heartbeat and pronounced, “She is gone.” I could not hold back the tears and fled to the porch. I found the clock under the chair, and saw that it was 12:51. How long was it since Zinnia died? Maybe three minutes, I thought. That means Zinnia died at 12:48. It hit me like a thunderbolt! Again the minute was marked at 48. Basil 5:48. Zinnia 12:48.

I returned to the bedroom, brought out the Paul Smith shoebox Terry had set aside, and the doctor’s attendant gently helped me cradle Zinnia’s lifeless body into the bed of soft white packing paper. I wondered if she noticed the wish bone I had put there that morning.

After the doctor left, Terry picked a bouquet of flowers while I removed the litter box to the garage, and brought the feeding and watering dishes there as well so he would not have to be the one who did this. Together we took the box to the hole beside the graves of Basil and Rufus, placed it in the bottom and shoveled the dirt down into the hole. Terry brought his vase of Zinnias and placed it on the grave.

Surrounded by the splendid garden that Terry had brought into existence, I said to him, “Here we are, two gay guys weeping over our dead pets. Somehow this seems very fitting. They are now forever in this garden they loved to watch over from the porch. I am so, so sad to see them gone, but so glad we had them in our lives. They were brought here, two foundling cats, born with FIV, so that two gay guys, living with HIV, would adopt them and and give them a good life nobody else would have done.”

RSS Feed

RSS Feed